The World’s Most Volcanic Islands: Exploring Iceland’s Lava Fields

Iceland sits directly atop the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, a location that defines its existence as one of the most geologically active places on Earth. This island nation contains over 30 active volcanic systems, a concentration of energy that constantly reshapes the terrain beneath the feet of its inhabitants. For the visitor, the landscape offers a stark, sensory experience: vast expanses of blackened earth, vibrant green moss, and steam rising from the ground.

Recent events, such as the 2021–2025 eruptions at Fagradalsfjall and the surrounding Reykjanes area, have brought this activity into sharp focus. These eruptions allow observers to witness the creation of new land in real-time. However, the environment here is defined by contrast. The “Land of Fire and Ice” is not just a slogan; it describes the physical interaction between subterranean magma and surface glaciers. This dynamic creates unique hazards and spectacular scenery found nowhere else.

Understanding Iceland’s physical geography requires looking at the geological history that dictates where people settle, the cultural respect developed over centuries for these volatile forces, and the necessary safety measures for traveling through such a raw environment.

Geological Wonders of Iceland’s Volcanoes and Lava Fields

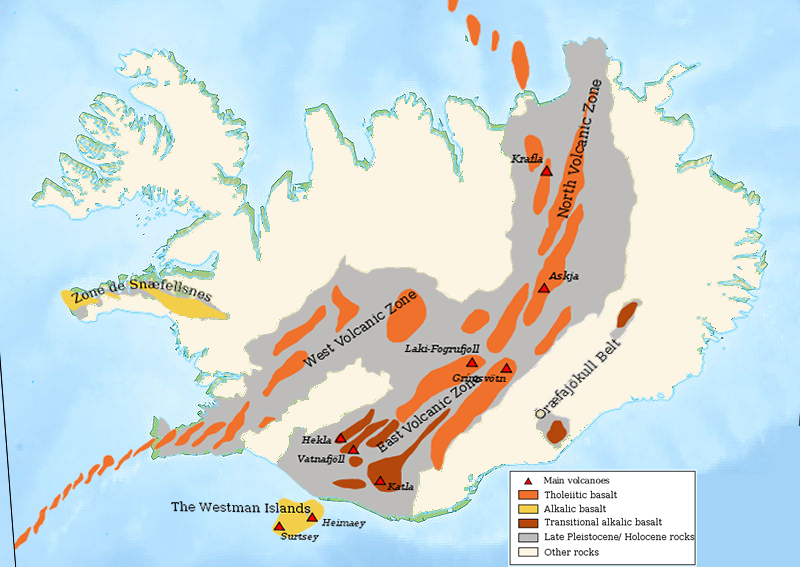

Iceland’s position at the divergence of two massive tectonic plates fuels its volcanic dynamism. To understand the landscape, one must first understand the materials that compose it. The two primary rock types you will encounter are basalt and rhyolite. Basalt is dark, dense, and rich in iron; it forms from runny lava and makes up the vast majority of Iceland’s lava fields. Rhyolite, conversely, is lighter in color, contains more silica, and is associated with more explosive, sticky magma, often found in the colorful highlands.

Formation and Tectonic Activity

The engine driving Iceland’s geology is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. This is a fracture on the ocean floor where the Eurasian and North American tectonic plates pull apart. They separate at a rate of approximately 2.5 centimeters (about 1 inch) per year.

Imagine a conveyor belt moving in opposite directions. As the plates separate, a gap forms. Unlike most places on the ridge which remain underwater, Iceland sits directly over a mantle hotspot—a plume of intense heat rising from deep within the Earth. This hotspot acts like a blowtorch, pushing the crust upward above sea level and supplying a constant stream of magma to fill the gap left by the separating plates.

This combination results in frequent eruptions, occurring on average every four to five years. The output is massive; lava fields cover roughly one-tenth of the country’s total area. The Reykjanes Peninsula serves as a prime example of this process. Recent fissure eruptions there have paved over valley floors with fresh rock, effectively adding new land to the island. While technology has advanced, volcanic predictability remains difficult. Scientists monitor seismic tremors and gas emissions to forecast activity, but the exact timing and location of a breach can still surprise even the experts.

Notable Eruptions and Lava Field Features

Current landscapes are best understood through the lens of historical eruptions. The 1783 Laki fissure eruption stands out as a catastrophic event that altered history. It lasted for eight months, releasing vast lava flows and a haze of toxic sulfur dioxide. The fallout killed livestock and caused a famine that claimed a large portion of the Icelandic population, while the haze lowered global temperatures.

Today, the Laki eruption is memorialized in the Eldhraun lava field. It is the largest lava flow from a single eruption in recorded history. Over the centuries, a thick layer of woolly fringe moss has blanketed the sharp rock, softening the dangerous terrain into a rolling sea of green. In the north, the Dimmuborgir lava fields offer a different aesthetic. Here, lava flowed over a wet marsh, causing steam explosions that created twisted, towering rock pillars. Locals often liken these formations to trolls or castles.

More recently, the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull demonstrated the disruptive power of these volcanoes. While the lava flow was relatively small, the interaction with the glacial ice cap created a massive plume of fine ash. This cloud grounded air traffic across Europe for weeks, illustrating the persistent duality of Iceland’s geology: it creates stunning scenery but poses distinct hazards to modern infrastructure.

Geothermal Phenomena and Landscape Diversity

The magma lurking beneath the surface does more than erupt; it powers extensive geothermal systems. Groundwater seeps down, hits hot rock, and returns to the surface as steam or boiling water. Deildartunguhver is the most powerful hot spring in Europe, pumping out 180 liters of boiling water per second.

The interaction between fire and ice also builds specific geological structures. When a volcano erupts underneath a glacier, the pressure and rapid cooling create hyaloclastite ridges—flat-topped mountains with steep sides. These subglacial volcanoes add vertical layers to the terrain. However, the environment remains fragile. The soil in these lava fields is often thin and sandy. Soil erosion is a constant issue; once the vegetation cover breaks, the wind can strip the land back to barren rock, making regrowth difficult.

Cultural and Historical Significance of Iceland’s Volcanic Heritage

The raw power of the land has fundamentally shaped the human experience in Iceland. Generations of Icelanders have not only adapted to these forces but have woven them into their identity, creating a culture that respects the volatility of nature.

Influence on Icelandic Culture and Folklore

In medieval times, settlers used stories to explain the unpredictable violence of the earth. The Sagas and the Eddas, ancient collections of Norse narratives, frequently depict volcanic landscapes as the realms of supernatural beings. The term “jötnar” refers to giants or mythical entities often associated with the chaotic forces of fire and ice. These stories served as a way to personify the dangers lurking in the mountains.

Modern culture continues this relationship but shifts the focus from fear to resilience and utility. Festivals and art exhibitions frequently center on the aesthetic of the lava fields. More practically, the geothermal energy derived from volcanic systems now powers nearly 90% of Icelandic homes. This shift has fostered a sustainable lifestyle where the same geological heat that once threatened survival now ensures comfort during the dark winters.

Historical Settlement and Adaptation

Since the arrival of Norse settlers in the 9th century, volcanic activity has dictated where people could live. Early inhabitants had to navigate hazardous terrain, avoiding active zones and settling in areas where lava had long since cooled to form harbors.

The 1973 eruption on the island of Heimaey in the Westman Islands is a definitive example of modern adaptation. A fissure opened without warning on the edge of the town, burying hundreds of homes in ash and lava. Rather than fleeing permanently, the community fought back. They used massive pumps to spray seawater on the advancing lava front, cooling it enough to save the harbor. In the aftermath, the town utilized the heat from the cooling lava to power their heating systems for years.

Outsiders often ask why people continue to live in such a volatile area. The answer lies in the benefits. Ash deposits from eruptions, once weathered, create highly fertile soil for farming. The geothermal resources provide cheap energy. Managing the risk is simply part of daily life, handled through rigorous community preparedness plans and evacuation drills.

Practical Guide to Accessing and Protecting Iceland’s Lava Fields

Visiting these geological sites requires preparation. The landscape is rugged, and the weather is changeable. Informed travel ensures that you can access these locations safely and leave them intact for future visitors.

Accessibility and Transportation Options

Iceland is located in the North Atlantic, serving as a connector between Europe and North America. Keflavík International Airport (KEF) is the primary entry point, situated on the Reykjanes Peninsula, meaning you land directly on a lava field. From there, visitors can utilize domestic flights from Reykjavík City Airport or an extensive bus network to reach popular sites like the Golden Circle.

For those wishing to explore remote lava fields, renting a vehicle is often necessary.

- Paved Roads: Route 1 (the Ring Road) circles the island and is accessible by standard cars.

- F-Roads: These are mountain tracks located in the interior (Highlands). By law, you must have a 4×4 vehicle to drive on roads marked with an “F” (e.g., F208). These tracks are unpaved, often steep, and require crossing unbridged rivers.

- Seasonality: F-roads are generally only open from late June to September. Winter travel requires specialized super-jeeps and distinct caution due to snow and limited daylight. Summer offers nearly 24 hours of daylight, allowing for extended hikes.

Travel Requirements and Safety Protocols

Iceland is a member of the Schengen Agreement. Travelers from the U.S., Canada, and many other nations can enter visa-free for up to 90 days. Always ensure your passport is valid for at least three months beyond your planned departure date.

Safety in volcanic zones is specific and serious.

- Gas Monitoring: Fresh lava fields release gases like sulfur dioxide (SO2) and carbon dioxide (CO2). These invisible gases are heavier than air and can accumulate in low-lying depressions or valleys. If you feel dizzy or smell strong sulfur, move to higher ground immediately.

- Digital Tools: Download the SafeTravel.is app and check the Icelandic Met Office website regularly. These sources provide real-time alerts on weather, road closures, and seismic activity.

Environmental Protection and Sustainable Practices

Icelandic moss is incredibly fragile. It can take decades to recover from a single footprint. The Nature Conservation Act protects these landscapes, making it illegal to drive off-road or damage vegetation.

- Leave No Trace: Stick to marked trails. Do not remove rocks or trample the moss.

- Geoparks: The Reykjanes Peninsula is a UNESCO Global Geopark. These areas promote education about biodiversity and geology.

- Mitigating Overtourism: Popular sites can become crowded. Consider visiting during shoulder seasons (May or September) or booking guided tours that take you to less-trafficked areas. This distributes the impact of tourism and often provides a deeper insight into the geology.

Traversing Iceland’s lava fields offers a rare perspective on the planet’s inner workings. It is a place where ancient geological forces meet a modern, vibrant culture. A visit here is a balance of thrill and caution, requiring respect for the environmental safeguards in place. As you walk across the solidified magma, you engage with a landscape that is still under construction, leaving you with a profound sense of wonder about the eruptions yet to come.

Further Readings & Resources

- Icelandic Environment Agency’s guide to volcanic sites and protection: https://ust.is/english/visiting-iceland/travel-information/volcanic-sites/

- Guide to Iceland’s detailed geology of lava fields and volcanoes: https://guidetoiceland.is/nature-info/geology-of-iceland

You may also like

A Guide to Eco-Friendly, Sustainable London

The Origin of Mount Kilimanjaro’s Name

Archives

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

Leave a Reply